Socorro Overview: 2021, presentation

Socorro became part of the Data Org part of Mozilla back in August 2020. I had intended to give this presentation in October 2020 after I had given one on Tecken [1], but then the team I was on got re-orged and I never got around to redoing the presentation for a different group.

Fast-forward to March. I got around to updating the presentation and then presented it to Data Club on March 26th, 2021.

I was asked if I want it posted on YouTube and while that'd be cool, I don't think video is very accessible on its own [2]. Instead, I decided I wanted to convert it to a blog post. It took a while to do that for various reasons that I'll cover in another blog post.

This blog post goes through the slides and narrative of that presentation.

Socorro Overview: 2021

Title slide

Socorro: Overview of the Mozilla crash ingestion pipeline. Presented at Data club, March 26th, 2021

Hi! I'm Will Kahn-Greene. I work on Socorro, the Mozilla crash ingestion pipeline, and it's spunky sidekick Tecken, the Mozilla symbols server. I, and my projects, joined Data Org in August 2020.

This presentation is a high-level overview of Socorro covering:

What is Socorro

Some things in the domain of crash reporting and crash ingestion that are nice to know

Roughly how Socorro is architected

Crash signatures

Some fun facts about crash reports and crash report data

Where to learn more

I hoped people came out of this overview with some new clarity on crash report processing, the crash report data set, and what I toil with day-to-day.

Slide 1

Section: What is this ... Socorro?

What do we mean when we talk about "Socorro"?

Slide 2

Socorro is the name of the Mozilla crash ingestion pipeline.

Socorro is the name of the Mozilla crash ingestion pipeline. It collects and processed crash reports sent by the crash reporting client after a Mozilla product like Firefox crashes.

"Socorro" is named after Socorro, New Mexico--the town near the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array.

I wasn't on the team at the time, but I imagine the reason it was named that was that Socorro was collecting signals from the universe which we can use to fix the product or something like that.

I carried this naming theme on. The collector is named Antenna. The processor rewrite which I semi-abandoned is named Jansky.

Slide 3

Socorro history

The Socorro project started in 2007. It's one of the older projects at Mozilla.

It's changed a lot over the years as needs and technologies changed.

It consists of a bunch of repositories with over 13,000 commits spanning 14 years by over 130 contributors.

The main repository is https://github.com/mozilla-services/socorro which has the processor, webapp, and a scheduled task runner. The collector is in https://github.com/mozilla-services/antenna. There are a handful of other repositories involved, too.

Slide 4

Fun fact about a pellet stove

On March 7th, 2016, not too long after I joined the Socorro project, we made a change that broke Lars' pellet stove. He hopped on IRC and told us [3]

Mar 07 15:45:14 <lars> my pellet stove fails now

Mar 07 15:45:44 <willkg> :(

Mar 07 15:45:52 <lonnen> lars: oh no!

Mar 07 15:46:48 <peterbe> lars: is that an euphemism for our intent of

splitting up socorro by function instead? :)

Mar 07 15:47:34 <willkg> maybe the pellet stove was importing parts of

socorro?

Mar 07 15:47:58 <lars> willkg: socorro is actually running my pellet stove

Mar 07 15:48:18 <lonnen> willkg: it absolutely was

Mar 07 15:48:49 <lars> peterbe: lonnen: I took the pellet stove branch and

updated with the new master and find that the unit tests fail.

Mar 07 15:49:15 <peterbe> Life of humans affect pellet stoves too.

Mar 07 15:49:19 <peterbe> ...it seems.

Mar 07 15:50:04 <lars> hmm. doesn't seem to want to load the new "socorrolib"

I later found out that Lars had a thermostat which would POST "crash reports" to a collector and processor that ran on a Raspberry Pi which operated the pellet stove.

Lars later rewrote his pellet stove automation system to use Mozilla Things which was a project he worked on after he rolled off the Socorro project.

On the one hand, I do feel bad that we broke Lars' pellet stove. On the other hand, the situation is wild! It never would have occurred to me that this could happen outside of a Monty Python sketch. It doesn't have much bearing on crash ingestion pipelines, but I included it because it's a fantastic story in the Socorro project.

One of the problems with presenting over Zoom is that stories like this get told to silence so I'm unsure about whether it was worth having in the presentation.

One of the things I liked about the IRC days is that I have logs of things and can refer to them later. After we ditched IRC, I have very few records of what happened. It makes archaeology like this impossible.

Slide 5

What is a crash report?

Let's go back a bit and talk about crash reports. What is it?

When a Firefox process crashes, the crash reporting client generates a crash report which consists of a set of key/value crash annotations and zero or more minidumps.

Annotations have names like "ProductName", "BuildID", and "MozCrashReason". They capture information about which product is running, what build/version/channel the build is from, information about the operating system and platform, and other things. Some of the values are strings. Some of them are JSON-encoded.

Slide 6

What is a minidump?

A minidump is a serialized form of information about the crashed process. It contains CPU register contents, bits of the heap, the addresses of the stack, the list of modules loaded, etc.

Minidumps are smaller than core dumps which makes them great for crash reporting.

We use the Breakpad library for creating and manipulating minidumps.

Slide 7

What's Breakpad?

Breakpad is a set of client and server components that implement a crash reporting system. Mozilla uses Breakpad to:

extract symbol information from binaries

collect information from a crashed process and serialize that as a minidump

POST the crash report to a server

extract information from a minidump and symbolicate frames

Slide 8

What do we do with crash reports?

Socorro collects crash reports sent by the crash reporting client, processes them, and stores them in ways we can use them. But what do we use them for?

Engineers look at individual crash reports to figure out what caused the crash. They can download the minidump and see the state of the process when it crashed. This helps us debug crashes our users had.

We also look at crash reports in aggregate. Socorro processing generates a crash signature for each crash report. We can use the crash signatures to group crash reports into buckets of similar causes. Then we can look at changes in those buckets over time.

Do crash counts for signatures change over time? Do we see a spike in crash count for a signature after a new release? Do we see a spike in crash count for a signature after a Microsoft patch Tuesday or a macOS update? Looking at this helps us see context and possible impact.

Slide 9

Crash reporting helps us build great products.

The Mozilla crash reporting system is a critical part of how we build software at Mozilla. It helps us find and fix issues we otherwise probably wouldn't have known about.

Slide 10

Section: Architecture

Now let's cover high-level architecture of Socorro.

Slide 11

Socorro consists of a collector, processor, webapp, and scheduled task runner

Socorro consists of:

a collector

a processor

a webapp called Crash Stats which users use to search and access crash report data

a scheduled task runner for maintenance

a bunch of libraries, tools, and other knick-knacks

The bulk of this is written using Python and is bespoke. We're not using processing pipeline systems like Airflow or Kafka.

Now that Socorro is part of the Data Org, I'm looking at re-architecting parts of Socorro to be more like what we're using for Telemetry.

Slide 12

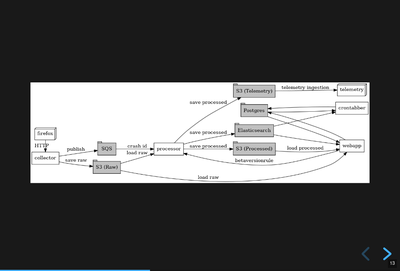

Architecture diagram

This diagram [4] shows the basic flow of crash report data.

Crash reports are accepted by the collector. They're "big" so the collector generates a crash id, saves the data to AWS S3, and tosses the crash id in the processing queue.

The processor watches the queue, pulls the data from AWS S3, processes the crash report, and saves the processed data back to AWS S3. It also indexes the processed data in Elasticsearch.

AWS S3 is where we store the raw and processed data.

Elasticsearch is the data store we use for aggregations and search results. It drives most of the analysis and discovery parts of the Crash Stats webapp.

We use Postgres for managing users and groups. We also maintain some bookkeeping about crash signatures that we build up over time. When was the first build id and date we saw this signature?

I have this thing about architecture diagrams: I really want them to be generated from a text-based source so I can maintain them and version them with the rest of the documentation. This one uses dot notation and graphviz. It's really tricky to get the diagram to flow from left to right, but this seems ok.

Recently, I looked at using mermaid.js, but I couldn't get it to build a diagram that flowed well.

Layout of connected objects on a 2D plane is something I studied a bit in grad school. It's a complicated problem.

Anyhow, some day I'll either find or build a tool that lets me create architecture diagrams using a text-based source that work well.

Slide 13

Section: Fun facts about crash reporting

When writing this section, I was thinking about how Mozilla has two different crash data sets: crash pings and crash reports. They have wildly different properties and the resulting data sets are pretty different.

Data Org maintains the crash ping data set and have for a long while. Socorro is new to Data Org, so now Data Org has both crash data sets.

Slide 14

Fun fact 1: we have two crash data sets: crash pings and crash reports

We have two sets of crash data. They're really different [5].

Crash pings are an opt-out data set. We get crash ping data any time Firefox crashes if the user hasn't gone out of their way to shut off sending data to Telemetry. The crash ping data doesn't have urls, email addresses, contents from memory, or a variety of other personally identifiable information in it.

It has the memory addresses for a stack and the list of modules that were loaded, but it doesn't have a minidump. Engineers can't look at a crash ping and know much about the state of the crashed process.

Because it's an opt-out data set, we get a lot more crash ping data than we do crash report data. I claim this means that the crash ping data is better for uses where you want to look at normalized counts over time and guardrail metrics like "crashiness".

We have some infrastructure to build to symbolicate the stacks of crash pings, generate crash signatures, and store that somewhere in a usable place. That's an ongoing project.

Crash reports are an opt-in data set. When Firefox crashes, the crash reporter client pops up a dialog and asks the users, "Do you want to submit this crash report to us?" or something to that effect. The user then has to click "submit" to submit the crash report. If the user doesn't click "submit", it doesn't get sent [6].

Because it's an opt-in data set, there are all kinds of reasons we may not get a crash report. I claim this means it's not representative of crashiness.

Because this data set has minidumps, engineers can download the minidumps and see the state of the crashed processes. That can be invaluable for debugging some kinds of problems.

One of the problems with crash reporting at Mozilla is the ambiguous terminology. "Crash ping" and "crash report" are stunningly unhelpful in communicating what they are, where they live, how they're different, etc. I'd love to adopt better terms, but I don't have any good ideas.

This is simplified. There are a few other settings involved and the user is able to opt-in to automatically submitting crash reports. I'm glossing over that for now because it doesn't change the fact that it's an opt-in data set.

Slide 15

Fun fact 2: Socorro throttles incoming crash reports

The Socorro collector has a series of throttle rules. Even if users opt-in to send their crash reports, the Socorro collector may reject them.

Generally, we don't want crash report data that isn't actionable.

For example, if the crash report is from a version of Firefox from 2016, that's probably not helpful; there's probably nothing we're going to do with that. Given that, I don't want to collect, process, or store it.

We don't look at all the crash reports for Firefox desktop current release because many of them are redundant since this is the version in wide use. The Socorro collector rejects 90% of incoming crash reports for Firefox desktop release channel.

There are a bunch of other throttle rules. We adjust them from time to time.

In this way, we're not collecting, processing, and storing data we're probably not going to use.

Slide 16

Fun fact 3: crash reports are big

Crash reports can be big. Because the minidumps are a chunk of memory, they can range in size. Crash reports for stack overflow errors can be bigger than 25mb.

On average, crash report sizes are around 600kb.

We keep track of sizes over time. Further, mobile products compress crash reports before sending them to reduce sizes. Firefox desktop will do this soon, too [7].

This is dramatically bigger than crash pings which are 2kb or thereabouts.

Or it already does--I forget which.

Slide 17

Fun fact 4: we reprocess crash reports

We regularly reprocess crash reports. This helps a lot when:

we've found and uploaded symbols for libraries we didn't previously have

we've tweaked the signature generation algorithm

we've fixed bugs in processing or stackwalking

Slide 18

Section: Let's talk about signatures

Crash signatures let us group crashes into buckets of like causes.

Slide 19

A bit about crash signatures

The processor generates a crash signature for every crash report.

Crash signatures let us group similar crash reports glossing over differences like:

compiler differences

operating system versions and changes in their libraries

architectures

GPUs

drivers

web sites

For example, on Windows, the library name might be xul.dll, but on Linux,

it's libxul.so. They're generated from the same source code, but the module

names are different.

Slide 20

Examples of crash signatures

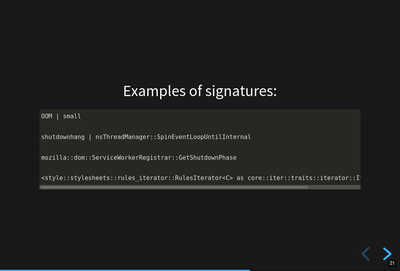

Here are four signatures.

The first one:

OOM | small

This is "out of memory after a small allocation". We get a lot of crash reports because of this. Generally they're not actionable.

The second one:

shutdownhang | nsThreadManager::SpinEventLoopUntilInternal

This is from a certain kind of shutdown hang. Firefox uses multiple processes and IPC to communicate between them. Processes come and go and sometimes when Firefox is shutting a process down, it hangs or doesn't communicate its state quickly enough. Technically, these aren't crash reports--they're a different kind of report.

The third one:

mozilla::dom::ServiceWorkerRegistrar::GetShutdownPhase

This is some kind of crash in the GetShutdownPhase method of something. The signature seems a bit skimpy to me on that one. I don't remember why I chose it for the slide.

The fourth one:

<style::stylesheets::rules_iterator::RulesIterator<C> as core::iter::traits::iterator::I...

This is a long signature that exceeds the rectangle. Crash signatures get truncated after 255 characters. Generally they're under 80 characters, but some can be lengthy.

The first two signatures have a | symbol. I think the fourth one has one,

too, but it's obscured. The | symbol separates parts of the crash

signature. Parts can be prefixed depending on annotation values in the crash

report. This is the case with OOM crashes. The parts can also be frames in the

stack of the crashing thread. Sometimes symbols can be really long, especially

symbols from Rust code.

Slide 21

Crash signature generation is finicky

This slide should get fixed. Crash signatures can be finicky, but generally the algorithm we're using is fine.

Too coarse and signatures aren't helpful because the crash reports with that

signature stem from a variety of different causes. The OOM | small

signature mentioned in a previous slide is like that. There are so many

different causes that it's not actionable. We chip away at it periodically.

Too fine and signatures aren't helpful. If a crash signature only ever applies to a single crash report and we get a million a week, then that signature will never show up in the Top Crashers report and we'll never see the crash report.

We tune the signature generation algorithm frequently. I'd say we make a change a week, but generally changes come in bursts especially when one of the engineering groups is spending their time focusing on crashes in their module area.

Slide 22

Section: crash pings and crash reports

Slide 23

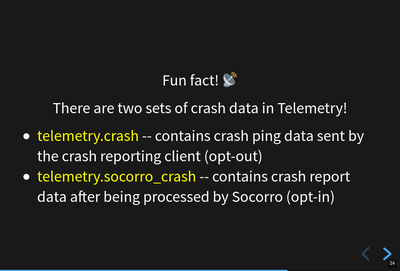

Fun fact: there are two sets of crash data in Telemetry!

I was giving this presentation to the Data Org which owns the crash ping data set and now owns the crash report data set so I figured I'd go into more detail about the differences.

Having said that, this feels like a repeat of a previous slide.

The names here (telemetry.crash and telemetry.socorro_crash) refer to

BigQuery tables and "Telemetry" refers to the data set generated by Telemetry

and Glean and the data processing pipeline and all that.

The Socorro processor processes crash reports and saves them to AWS S3 and

Elasticsearch. We talked about those earlier. It also saves crash report data

to another AWS S3 bucket where it's ingested and put into the

telemetry.socorro_crash BigQuery table by an Airflow job that runs once a

day.

Theoretically, that enables us to use the same data analysis tools we use for

Telemetry on Socorro's crash report data. I know the

telemetry.socorro_crash table gets used for computing correlation data for

crash signatures. I use it occasionally when BigQuery SQL is more convenient

than Supersearch to query things. I don't know if it's used for anything else.

Slide 24

But that's a talk for another day.

A while back, I wrote a blog post on crash pings vs. crash reports. I think some of that is outdated and some of it was probably wrong when I wrote it.

It's a complicated topic that probably deserves its own presentation.

Slide 25

Section: what's the data like?

Let's talk about what the data looks like.

Slide 26

Crash report data is generated when the process is crashing

We get a crash report when a process is crashing. Because of the way the crashed process data is captured, the resulting crash report can be all kinds of exciting!

Slide 27

Crash report data is generated when the process is crashing--continued

We see all kinds of things in the data:

Values are mangled, there are nulls, the impossible happens, JSON is more like JaSon

Memory is bad, so values stored in bad memory don't make any sense

Bitflips in the program code

We get crash reports from:

extremely old versions sent miraculously from stone tables

competitors software

Crash reports are generally OK and when they're not, sometimes the grossness itself is a helpful signal.

Slide 28

Crash report data is toxic

Because crash reports contain bits of memory from the heap, they can contain any kind of data. Having said that, I don't think I've seen 2021h1 OKRs in a crash report before.

Slide 29

We're persnickety about the data

We have a protected data access policy and a process for giving people access. Most people don't have access to protected data.

We keep crash report data for 6 months or so. After that, it's deleted by automated processes.

There have been occasions when we discovered we collected data we should not have. In one instance a few years back, we dumped all the crash report data. In other instances, we ran a script that removed specific annotations from crash reports that had them.

Slide 30

That's it!

Slide 31

The truth is out there

I did this a while back with the intention of using it as a Socorro sticker. It would have been a cool sticker.

Slide 32

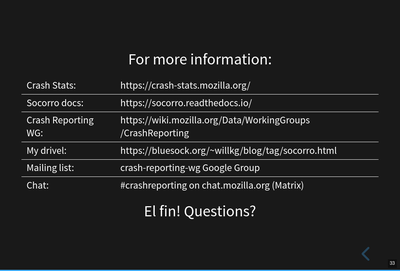

For more information ...

This slide is a bit of a smorgasbord of stuff. I didn't know what stuff was important for whoever might be looking at this slide.

I think if you know these, you can find the others:

Crash Stats website: https://crash-stats.mozilla.org/

Crash Reporting WG: https://wiki.mozilla.org/Data/WorkingGroups/CrashReporting

This slide also has "Questions?"

If I recall correctly, the questions/comments were these:

Chutten corrected me on whether shutdownhangs send a crash ping. I wasn't sure if they did or not. Chutten said they definitely do.

Dan asked if crash signatures were Mozilla-centric. This is an interesting question and has some subquestions. It used to be the case that Socorro was a generalized crash ingestion pipeline and it was intended for anyone to use it. When I started in 2016, I determined that maybe other groups use it, but they don't participate in its development, aren't part of a users list, and I have no way to contact them to announce changes or ask questions about usage or anything. That's not a sustainable position to be in, so I changed the project to be Mozilla's crash ingestion pipeline. It's fine if other groups used it, but I wasn't going to support them or consider them when making changes.

Because of that, I made a lot of Mozilla-centric changes to the codebase. It's definitely possible to generalize them out again, but I don't think I'm going to do that unless there's a compelling reason to.

That's true of signature generation, too. There are parts of the signature generation code that would work for anyone, but part of signature generation is specific to how Mozilla builds Mozilla products. We could generalize that out and I don't think that work is hard, but I don't think I'm going to do that unless there's a compelling reason to.

El fin

That's it! If this blog post version of the presentation is helpful to you, let me know!