Socorro Smooth Mega-Migration: retrospective (2018)

Project

- period:

-

1.5 years

- impact:

vastly reduced technical debt

vastly improved developer efficacy

reduced infrastructure security risks

Summary

Socorro is the crash ingestion pipeline for Mozilla's products like Firefox. When Firefox crashes, the Breakpad crash reporter asks the user if the user would like to send a crash report. If the user answers "yes!", then the Breakpad crash reporter collects data related to the crash, generates a crash report, and submits that crash report as an HTTP POST to Socorro. Socorro collects and saves the crash report, processes it, and provides an interface for aggregating, searching, and looking at crash reports.

Over the last year and a half, we've been working on a new infrastructure for Socorro and migrating the project to it. It was a massive undertaking and involved changing a lot of code and some architecture and then redoing all the infrastructure scripts and deploy pipelines.

On Thursday, March 28th, 2018, we pushed the button and switched to the new infrastructure. The transition was super smooth. Now we're on new infra!

This blog post talks a little about the old and new infrastructures and the work we did to migrate.

Why switch this time?

First, some context. Way back in the day, Socorro was hosted in a Mozilla data center on long-running virtual servers running CentOS. The hardware was out-of-warranty and dying, so work was under way to figure out the next infrastructure. Then the plan changed and that datacenter was scheduled for decommission and the Socorro team had to scramble to move it somewhere else.

They decided to move it to AWS, but the timing was such that they didn't have much time to re-architect and rebuild Socorro to work well in AWS. For the purposes of expedience, they opted for a hybrid approach between the old way of doing things on servers in the datacenter and doing things with AWS best practices.

The new infrastructure was vastly improved from the one before it. Developers had a lot of autonomy and visibility into the complex system. Deploys were simpler and more automated. Nodes could be resized to be larger as computational requirements changed. There were scaling groups so an increase in load could be handled by throwing more nodes at it. So on and so forth.

That migration project was considered a success. I wasn't on the project at the time, but I was sitting at the next table over at the All Hands when they finished the migration. It was cool stuff.

However, the hybrid approach resulted in a unicorn infrastructure that was unlike anything else at Mozilla. It was cute, but quirky, in some ways and really awkward in others. The plan was never to leave it in this state, but to incrementally change it into a more AWS-like system over time. We worked on that for a while, but it became clear that it would be easier to build a new infrastructure and migrate rather than continue to iterate on the existing one.

Let's talk about some of the quirky and awkward things about the old infrastructure.

Complicated deploy pipelines and confusion about deploy artifacts. Deploys to stage happened automatically any time we merged to the master branch. These would build an RPM of Socorro components, install the RPM on CentOS, bake an AMI, and push that out to stage. Deploys to prod happened by tagging a commit in the master branch. The AMIs associated with that commit would get pushed to prod. RPM filenames included the tag of the Socorro build it was built on. However, since RPMs were built in the deploy to stage and the tag was created to deploy to prod, the RPMs that were in prod had the previous tag. That was constantly confusing for me.

Local development, stage, and production envirionments were too different. Our local development environment was completely different from the stage and production environments. It was really hard to get them to more closely match stage and production. Periodically, we'd have problems in stage and production that we couldn't reproduce locally and vice versa.

Because migrations and configuration changes were done manually, our stage and production environments weren't like one another. Over the years, some changes to be done were forgotten and the environments diverged. I had several instances where a migration I wrote would work fine on my local machine, work fine on stage, but fail in production because there was a stored procedure or a table with foreign keys that didn't exist in other environments.

Long running admin nodes with manual (often forgotten) updates. Both stage and production had a long-running admin node that we updated manually after deploys. Further, we had to manually run migrations and do configuration changes.

Configuration was unwieldy and not tracked. Configuration was managed in Consul. We had 170+ environment variables (some with structurally complex values > 100 characters long) per environment controlling how Socorro worked. Configuration data wasn't version controlled and had a "review process" that consisted of conversations like this:

<willkg> can someone review this config change? <willkg> consulate kv set socorro/processor/new_crash_source.new_crash_so urce_class=socorro.external.fs.fs_new_crash_source.FSNewCrashSource * peterbe looks. <peterbe> looks ok to me. * willkg makes the change. <willkg> done!

Since we weren't running Consul in the local development environment, configuration changes were effectively tested in stage.

One nice thing about Consul the way we had it set up was that after a configuration change, Consul would restart all the processor processes immediately--we didn't have to wait for a deploy. That made the occasional feature-flipping or A/B testing a lot easier.

Logs only existed on instances. Logs were created and existed on the instances. There was no log aggregation and no central storage. To look at logs, we'd have to log into individual nodes. Every time we did a deploy, we'd lose all the logs. Thus we could never look very far back in time at logs.

Processor cluster didn't auto-scale. The processor nodes were in a fixed autoscaling group and didn't scale automatically. Periodically, something in the world would happen and we'd get a larger-than-normal flow of crashes and the processors would be working furiously, but the queue would back up and our ops person would have to manually add nodes to the group. After a deploy, it'd return to the original number and we'd have to manually scale it up again.

Periods in AWS S3 bucket names. Ugh.

We use AWS S3 for storage of crash data. However, when we set that up years ago,

we put periods in our bucket names. For example, we had a bucket like

org.allizom.crash-stats.rhelmer-test.crashes. That becomes a problem when

you're using HTTPS because the SSL wildcard certificate creates problems.

Too much access to too many things. Another thing we wanted to do was further reduce which things had access to what storage systems. Reducing access would reduce the likelihood of security breaches and data leaks.

In summary, we had a list of things that we wanted:

aggregated, centralized logs and log history

Docker-based deploys

no more manual post-deploy steps leading to diverging environments

disposable nodes

configuration that was in version control along-side code and infrastructure and requiring review of changes

reduced access to storage systems

automatic scaling

AWS S3 bucket names that don't have periods

Knowing what we wanted out of a new infrastructure, we set about moving forward.

Why'd it take a year and a half?

It took a year and a half because there was a lot that needed to be figured out, a lot to change, and you can't rush baking a cake. Also, the team changed over that time as people rolled on and off the project.

What's involved in baking this cake? A lot of steps.

We split out the Socorro collector as a separate project. The collector is the part of the crash ingestion pipeline that accepts incoming crash reports and saves the crash data. As such, it has a different uptime requirement than the rest of the system. Splitting it out into a separate project with its own deploy pipeline made this project a lot easier and a lot less risky. (See Antenna: post-mortem and project wrap-up)

We stopped supporting Socorro for non-Mozilla users allowing us to remove swaths of code we didn't use. "Socorro" was both Mozilla's crash-ingestion pipeline as well as an Open Source project for building crash-ingestion pipelines for other people to use. In order to maintain backwards compatibility, we had been piling on new features, generic implementations of APIs, backwards-compatible shims, HTTP url redirects, and other similar things almost monotonically for years.

I never met anyone else who ran Socorro, nor did I figure out how to find out who they were and interact with them. As far as I could tell, we were drowning in a backwards compatibility marsh for an Open Source project that had an unknown user base that didn't participate in its maintenance.

The Socorro codebase was HUGE and vast swaths of it weren't used by us--it was the Gormenghast of systems! We had a small team. We desperately needed to make Socorro maintenance easier. To do this, we needed to end Socorro-the-product. We made the decision to make it explicit that we were no longer supporting other Socorro instances.

That empowered us to remove parts of Socorro we weren't using and peel away layers of unused features and backwards-compatible grime that had accumulated over the years. We removed tens of thousands of lines of code. We removed a lot of complexity. We removed dozens of stored procedures, database tables, database views, classes, Python libraries, HTTP views, models, API endpoints, and a variety of other things. ([bug 1361394], [bug 1314814], [bug 1424027], [bug 1424370], [bug 1398946], [bug 1387493], Socorro in 2017, etc)

Folded the middleware into the webapp to centralize ownership of data storage. We finished the work to fold the middleware functionality into the webapp and removed the middleware component. ([bug 1353371])

Moved Super Search fields definition from being stored in Elasticsearch to a Python module. This unified Super Search fields and definitions across our environments. ([bug 1100354])

Updated Python dependencies and redid how we managed them. We switched to requirements files. ([bug 1306731])

Updated JavaScript dependencies and redid how we managed them. We switched to npm. ([bug 1388593])

Redid the local dev environment using Docker. This let us set it up so it was behaviorally like stage and production. That let us build and debug in an environment very similar to our server environments. That let us move a lot faster. (Socorro local development environment)

Cleaned up and improved crontabber. We unified crontabber configuration and then audited crontabber and all the jobs it was running so that we could run crontabber on a disposable node. ([bug 1388130], [bug 1407671])

Audited and cleaned up configuration. We audited configuration across all environments and removed some configurability of Socorro by making it less general and more "this is how we run it at Mozilla". We moved a bunch of configuration into Python code. We audited configuration and reduced reduced the differences between local development, stage, and production environments. ([bug 1296238], [bug 1434132], [bug 1430860], [bug 1434133])

Audited and cleaned up database state. We audited the databases across all environments and made sure they had the same contents (tables, views, stored procedures, lookup table contents, etc). ([bug 1435313])

Wrote a secure proxy for private symbols data. We threw together a proxy to allow minidump stackwalker access to the private symbols data for stack symbolication. ([bug 1437928])

Cleaned up stackwalker configuration. We redid how minidump stackwalker was configured and unified that configuration across all environments. ([bug 1407997])

Moved a ton of data. We had to figure out how to move 40 TB of data [1] from one AWS S3 bucket to another (and in the process discovered we had crappy keys--boo us!). We had problems with S3DistCp crashing after running for hours without doing any copying. We had more success with s3s3mirror.

Wrote a lot of scaffolding maintenance code. We had to write a bunch of code to maintain data flows for some data I'm not going to mention that's a royal pain in the ass. It now resembles an MC Escher drawing, but it "works". I can't wait for it to go away.

Wrote new pipelines. We wrote new deploy pipelines and Puppet files and templates.

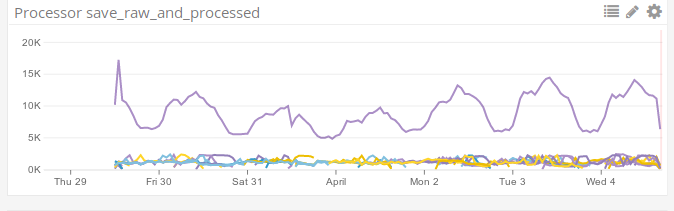

Implemented new autoscaling. We figured out autoscaling rules for processor and webapp nodes.

Implemented dashboards. We set up new dashboards in Datadog, new RabbitMQ accounts and queues, a new Elasticsearch cluster, new RDS instances, new AWS S3 buckets, monitors, alerts, deploy notifications, and so on. ([bug 1419549], [bug 1419550], [bug 1425925], [bug 1426148], [bug 1438288], [bug 1438390])

Wrote lots and lots of bugs, plans, checklists, etc. We wrote migration plans, load test plans, system comparison/verification scripts, system checklists, tracker bugs, and meta tracker bugs. ([bug 1429534], [bug 1429546], [bug 1439019], etc)

Set up and ran load tests. We ran load tests. We tweaked things and ran some more.

Meetings. We had meetings--tons of meetings! Pretty sure we had meetings to discuss when we should have meetings.

We did all this while maintaining an existing infrastructure and fixing bugs and adding features.

Where are we at now?

On March 28th, we cut over to the new system:

Last days of disco....

New infrastructure!

We had the minorest of minor issues:

I forgot that the data flow for the thing I shall not name and despise because it is the unholiest of unholy things works differently in production than all the other environments and when we cut over, we needed to manually tweak the crontabber record for it so that it would run correctly on Friday. We discovered the issue after a few hours, tweaked the crontabber record, and we're fine now.

We discovered there was a bug in this thing we decided to rewrite wherein the process ends before it has time to ack the crashes in RabbitMQ that it just pushed. The next time it starts up, it runs through the same crashes. Again. And Again. And Again. Every two minutes. Then on Sunday, those crashes started raising IntegrityErrors since the date embedded in the crash id did match the

submitted_timestampand so the processor was trying to jam it in the wrong database table. We shut it off and now that's fine.We discovered we needed to raise the nginx upload max file size for the reverse proxy that sits in front of Elasticsearch because some crashes are big. Like, really big. We raised it. Those crashes are saved to Elasticsearch now. Now that's fine.

We had to wait for the last S3 mirror to finish which took a couple of days. During that time, we were missing some crash data that had been collected and processed last week but was indexed in Elasticsearch, so it was searchable, so only sort of missing. We knew this and had notified users accordingly. This is fine now.

All minor things--no data loss. The equivalent of moving from one mansion to another mansion in four hours and in the process misplacing your golf clubs in the shower stall of the bathroom for ten minutes. Nothing broke. No data loss. No biggie.

This was a successful project. There are some minor things left to do. This unblocks a bunch of other work. Things are good.

We probably could have done better. We did some of the work a few times and if we did it "right" the first time, we might have finished earlier.

We had a lot of failures caught by simulations, tests, loadtests, runthroughs of system checklists, Sentry error reporting, Datadog graphs, and other places.

It's likely we'll hit some more issues over the next few weeks as we get a feel for the new system.

Still, it feels good to be done with this project.

Blog posts of past migrations

While working on this post, I uncovered posts from past infrastructure migrations:

April 20th, 2009: Socorro Dumps Wave Goodbye to the Relational Database

May 15th, 2009: Socorro Moves to New Hardware

January 1st, 2011: The new Socorro

January 21st, 2011: Socorro Data Center Migration Downtime

January 17th, 2015: The Smoothest Migration

I didn't find one from the last big migration which I think was June or July of 2015.

If you know of others, let me know. It's neat to see how it's changed over the years.

Thanks!

Members of the team over the period we built the new Socorro in lexicographic order:

Adrian Gaudebert, dev

Brian Pitts, ops

Chris Hartjes, qa

Greg Guthe, security

JP, ops

Lonnen, manager, dev

Matt Brandt, qa

Miles Crabill, ops

Peter Bengtsson, dev

Good job!

Also, thank you to Miles, Brian, Mike, and Lonnen for proofing drafts of this!